Skull Fractures (Cranial Fractures)

Last Updated on August 12, 2024 by The SportsMD Editors

Skull fractures (also known as cranial fractures) can occur in any sport in which hard objects are flying at high speeds. Fractures to the skull can occur in the anterior skull (facial fractures), top, sides, or in the back of the skull (basilar fractures).

including traumatic brain injury, subdural hematoma, epidural or extradural hematoma, or traumatic intracerebral hematoma/contusion. These injuries may be life-threatening requiring immediate medical assistance to stabilize and minimize the amount of possible damage to the brain.

Types of skull fractures

There are three categories of skull fractures including linear fractures, comminuted fractures, and depressed fractures. Linear fractures are considered simple fractures as the skull fractures in one line as may be seen in a broken nose (nasal fracture). These tend to heal without complications.

Comminuted fractures are those in which the bone shatters into multiple pieces. Comminuted fractures can be categorized as depressed fractures if the bone pieces are driven inside the skull.

Fractures with multiple bone pieces can have a secondary risk of bacterial infection if there is a break in the skin associated with the fracture. A bacterial infection in the intracranial cavity can result in a life-threatening condition known as septic meningitis.

Depending on where the fracture is located, bone fragments can actually penetrate the brain causing additional brain injury. Specific nerves can be damaged depending on the location of the injury. For example, if the fracture is in and around the eyes, the bone fragments may cause damage to the optic or olfactory nerves affecting the athlete’s ability to see or smell.

Symptoms of skull fracture

The best clue as to the possibility of a skull fracture is the mechanism of the injury (MOI). Sports medicine professionals are specifically trained in understanding the mechanisms of injury that result in sports injuries. The lesson learned is that if the force that caused the injury is sufficient to break a bone, then one should suspect a skull fracture.

If the mechanism was sufficient to cause a serious injury (i.e., hit in the head with a bat, line drive ball, or a fall onto a hard surface), then all staff involved in the sport should immediately follow their emergency action plan (EAP) and begin to provide emergency aid for the athlete.

Symptoms that may be seen with skull fractures include the following:

• Visible deformity (depression; although this may be disguised by localized swelling)

• Deep laceration or severe bruise to the scalp

• Palpable depression or crepitus (grating sensation)

• Unequal pupils (window to the brain)

• Discoloration under both eyes (raccoon eyes) or behind the ears (Battle’s sign)

• Bleeding or clear fluid (cerebrospinal fluid) from the nose and/or ear

• Loss of smell

• Loss of sight or major vision disturbances

• Unconsciousness for more than two minutes after a direct blow to the head

Who gets skull fractures?

Athletes may be at risk for skull fractures if they are involved in sports in which head protection is not worn or in sports in which heavier sports equipment is used. For example, although baseball and softball athletes wear helmets when they are on deck or at bat, players who are in an exposed dugout may be subject to head injuries from an errant foul ball or from a thrown bat.

Another example of an at risk athlete, how many facial/skull fractures have occurred in the past year from pitchers who have been directly hit in either the face, side or back of the skull from line drives hit right back up the middle? Pitchers in both baseball and softball are primary targets for skull injuries because of their distance from the plate and their inability to react quickly enough to defend their heads at the speeds the balls are traveling.

Golf is another sport in which a small hard ball is hit by a relatively larger object. A direct hit by a golf ball is enough force to cause a depressed skull fracture.

Although helmets are required in some sports, helmets are only recommended in other sports. For example, several deaths have occurred from traumatic head injuries from pole vaulters when the vaulter over or undershoots the protective landing pads and lands headfirst on the cement.

The family of one athlete who died from head injuries from pole vault started a foundation that raised money towards the design and construction of a helmet exclusively for pole vaulters. This helmet is not required, but hopefully will be gaining popularity in the coming years.

Sports in which athletes are not required to wear helmets but who regularly perform in the air are also at risk for skull fractures. These sports include cheerleading, gymnastics, basketball, and diving.

Prevention of skull fracture

Reducing the risk of skull fractures in sports will vary with the sport. In sports that require helmets, it is important that the athlete maintain a properly fitted helmet and that it is secured correctly.

In sports in which helmets are only “recommended” but sports in which skull fracture is a risk (pole vault), it may be wise for the athlete to invest in the recommended equipment considering that a brain injury can permanently remove the athlete from sports.

Parents of athletes need to also be aware of safety considerations for each sport. For example, the sport of cheerleading has obtained a significant amount of attention lately with the report that it is the most dangerous sport for young girls because of the high incidence of catastrophic injuries.

Parents of cheerleaders need to research the current safety recommendations and ensure that their child only performs stunts/tumbling on approved protective mats (not gym floors, artificial turf, grass, or rubberized track) and that his/her coach has been trained and has specific experience in stunting/tumbling progressions and spotting. Read about safety recommendations in cheerleading.

Preventing Catastrophic Injuries in Cheerleading

Seeking State and National Safety Standards for Competitive Cheer

If a program is not following current safety protocol, parents can remove their children from the program that does not adhere to proper safety precautions and place them into one that does. As fun as it is for the young athletes to fly in the air, landing on their head on a hard surface can quickly end their sport experience.

A unique piece of protective gear recently seen in softball programs is the use of protective face masks for pitchers. With the high numbers of fastpitch softball pitchers taking direct hits from line drives, this may be a growing trend. A number of protective face masks can now be found on the market specifically for pitchers.

Even with all of the safety equipment and safety precautions in place, catastrophic injuries can and do still occur in sports. However, with a practiced emergency plan in place, when a life-threatening injury does occur, the amount of secondary damage and injury to the athlete can be minimized.

What should I do if I suspect an athlete has a skull fracture?

The best care for an athlete suspected of a serious injury is for the coaching staff to immediately follow the steps in their EAP. If a sports program does not have a written EAP, the organizers/administrators need to get one in place immediately.

A number of things need to simultaneously occur when an athlete sustains a life-threatening injury. These steps include:

• Contacting emergency medical services (EMS) with exact location, type of injury, age of the athlete, and status of the athlete (unconscious, breathing, pulse)

• Providing immediate medical care to the athlete.

• Clearing the area of all athletes and non-essential people.

• Contacting parents if they are not on-site

• Pulling the athlete’s emergency medical information card to provide (EMS) with important medical history

• Sending one person to meet EMS and ambulance and direct them to the site of the athlete

• Retrieving medical supplies and bringing them to the scene

• Assisting the parents of the athlete if necessary

When an athlete sustains a serious head injury, the first concern of the first responders is to ensure that the athlete is breathing and has a pulse. With a significant head injury, one individual should immediately stabilize the head and neck while the other performs an initial primary evaluation (check for airway, breathing, and a pulse) of the athlete.

The head and neck should be stabilized (first responder’s forearms on either side of the head with his/her hands grasping the top of right and left shoulders) in the event that the athlete may have an associated spinal cord injury. When a serious head injury has been sustained, one should always suspect a possible spinal cord injury until it has been ruled out.

If the athlete is not breathing and does not have a pulse, rescue breathing and cardiopulmonary resuscitation should be immediately started. If the athlete’s vital signs are stable, then they should be retaken every few minutes and monitored until EMS arrives on scene.

If there is an open wound on the athlete’s head, sterile gauze should be gently applied (without applying pressure to the wound) to cover the wound. The wound should be covered to prevent the possibility of infection.

Treating for shock is another important component for a seriously injured athlete. If the athlete is conscious, the first responders need to talk with the athlete (in low and soft tones) to help the athlete remain calm. The first responder should reassure the athlete that help is on the way and that the responding team will continue to stay with the athlete.

What conditions may be associated with skull fractures?

Anytime a skull fracture has occurred, the underlying brain tissue is a risk for serious injury also. The brain injuries that may be associated with a skull fracture include focal cerebral conditions including epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, and cerebral contusion.

Because of the life-threatening nature of the possible associated brain injuries, immediate consultation with a neurosurgeon is usually indicated as soon as diagnostic images are completed.

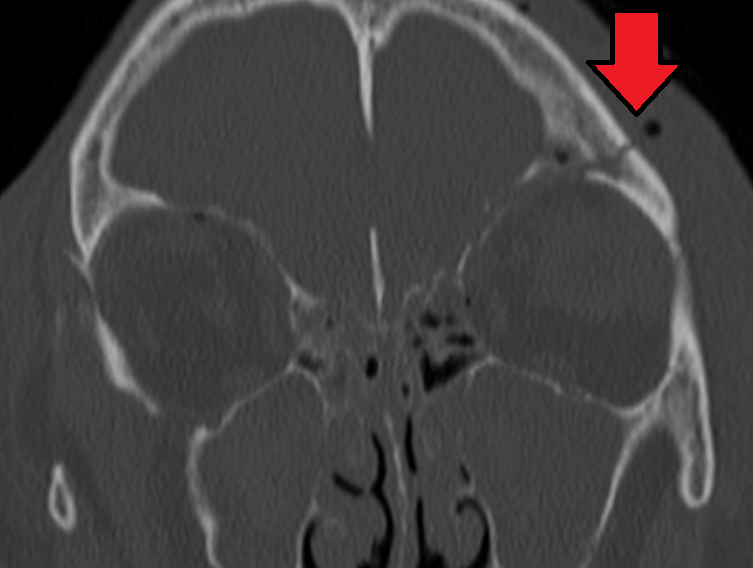

Diagnosing skull fractures

A skull fracture is diagnosed with a plain skull x-ray. Underlying brain injuries can be diagnosed with a CT scan.

Management of skull fracture

If an epidural or subdural hematoma is diagnosed through the CT scan, then a neurosurgeon should be consulted to remove the blood accumulating in the brain.

Simple linear skull fractures may heal in a few months to a year. Complex fractures with associated traumatic brain injury may take significantly longer with the prognosis dependent on the amount of brain injury.

Getting a Second Opinion

A second opinion should be considered when deciding on a high-risk procedure like surgery or you want another opinion on your treatment options. It will also provide you with peace of mind. Multiple studies make a case for getting additional medical opinions.

In 2017, a Mayo Clinic study showed that 21% of patients who sought a second opinion left with a completely new diagnosis, and 66% were deemed partly correct, but refined or redefined by the second doctor.

You can ask your primary care doctor for another doctor to consider for a second opinion or ask your family and friends for suggestions. Another option is to use a Telemedicine Second Opinion service from a local health center or a Virtual Care Service.

Can Telemedicine Help?

Telemedicine is gaining popularity because it can help bring you and the doctor together quicker and more efficiently. It is particularly well suited for sports injuries and facilitating the diagnoses and treatment of those injuries. Learn more about speaking with a sports specialized provider via SportsMD’s 24/7 Telemedicine Service.

References

- ABC News. (January 5, 2010). The Most Dangerous Sport of all may be Cheerleading. Nightline.

- Anderson, M., Hall, S., & Martin. M. (2009). Foundations of Athletic Training: Prevention, Assessment and Management. (4th Ed.). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA.

- Bahr, R. & Maehlum, S. (2004). Clinical Guide to Sports Injuries. Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL.

- Greene, J. (March 16, 2010). High School Baseball Player in Coma after Line Drive Hit. NBC Bay Area.

- Mueller, F., and Cantu, R. (August 19, 2008). National Center for Catastrophic Injury: 25th Annual Report. University of North Carolina.

- Rohlin, M. (March 31, 2010). Softball: El Toro Pitcher Kristi Denny Recovering from Line Drive to the Head. Los Angeles Times Insider, California.

- Schwartz, J. (April 6, 2010). Injured Marin Prep Pitcher Leaves MGH; Sent to Rehabilitation Facility in S.F. Marin Independent Journal. http://www.marinj.com.

- Shields, B. & Smith, G. (November, 2009). The Potential for Brain Injury on Selected Surfaces Used by Cheerleaders. Journal of Athletic Training 44(6).

- Zeigler, T. (October 2, 2009). Pole Vaulting Helmet Now Available. http://www.suite101.com.

- Zeigler, T. (September 7, 2009). Pole Vaulter Dies from Head Injury. http://www.suite101.com.