Sciatic Pain Associated with Lumbar Disc Conditions

Last Updated on November 14, 2024 by SportsMD Editors

Acute and chronic back pain is common in athletic and recreational athletes. While many back injuries in athletes can be attributed to muscle strain, some athletes can suffer from a painful condition involving inflammation of the sciatic nerve.

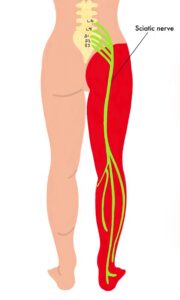

Understanding the path of the sciatic nerve and the muscles that it innervates will help the athlete to understand what happens when the nerve is compressed or inflamed because the pain will often follow the nerve path.

The sciatic nerve is the longest nerve in the body comprising a group of spinal nerves (L4 – S3) that travel from the spinal cord across the posterior pelvis and down the back of the leg. This group of nerves begins at lumbar vertebrae four (L4) and continues to branch out between the descending vertebrae down through the third sacral vertebrae (S3).

Portions of the sciatic nerve innervate the muscles of the buttock, posterior thigh, and lower leg. The sciatic nerve is actually composed of both the tibial nerve (innervates most of the muscles of the posterior leg) and the peroneal nerve (innervates the biceps femoris and portions of muscles of the lower leg).

What is sciatic pain?

Sciatica is an inflammatory condition of the sciatic nerve that can be caused by a number of conditions including herniated disc, muscle-related disease, spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal foramen), facet joint pathology (small gliding joints on either side of each vertebrae motion segment), or compression of the sciatic nerve between the piriformis muscle (deep external rotator of the hip) (Anderson, M.K., Hall, S.J., & Martin, M., 2005).

While sciatic pain can be caused by a number of conditions, the most common cause of sciatic pain is pain associated with a herniated disc (Bahr, R. & Maehlum, S., 2004). The neurological symptoms (radiating pain down the leg, weakness, numbness, tingling) that are felt by the patient are often related to the compression of the nerve root from the herniation of the disc.

An intervertebral disc is made up of two components. The inner portion of the disc is called the nucleus pulposus. It is surrounded by the outer portion known as the annulus fibrosis. Each is structurally different with each portion specifically designed to meet the demands of its function.

The nucleus pulposus is a dense, viscous substance designed to absorb compressive loads and act as the shock absorber for the spine. The annulus fibrosis is composed of strong, fibrous tissue laid down in different directions surrounding the nucleus pulposus.

Along with aiding the nucleus pulposus in absorbing compressive loads, the annulus fibrosis plays a role in containing the nucleus pulposus material inside the disc and in restricting the range of motion of the vertebral motion segments during extreme motions of the spine. However, a tear in the annulus fibrosis can allow a space for the nucleus pulposus to leak out and compress other soft tissues in the area.

While there are several classifications of disc herniation, the sciatic nerve can be compressed when a tear occurs in the outer portion of the disc allowing some of the material from the nucleus pulposus to protrude out of the disc and impinge on the nerve root.

Because the intervertebral disc itself is not innervated (does not have sensory nerves), the tear itself does not cause any pain. The pain occurs from the pressure of the herniated material on the surrounding tissues. Specifically, when the herniation of the nucleus pulposus impinges on the sciatic nerve, the athlete may experience both sensory (i.e., numbness and/or tingling sensations) and/or motor (weakness of a muscle or muscle group) deficits that follow the sciatic nerve pathway.

Classifications of sciatic pain

The signs and symptoms of sciatic pain may include radiating pain (pain that radiates down the back of the pelvis and leg following the nerve pathway) with the radiating pain possibly worse than the lower back pain (depending on the cause). The pain may increase when the patient coughs, sneezes, strains, sits or leans forward.

The signs and symptoms of sciatic pain may include radiating pain (pain that radiates down the back of the pelvis and leg following the nerve pathway) with the radiating pain possibly worse than the lower back pain (depending on the cause). The pain may increase when the patient coughs, sneezes, strains, sits or leans forward.

The athlete may also experience numbness and tingling down the leg with associated muscle weakness. To attempt to minimize the discomfort, the athlete may walk with a noticeable limp and with a side tilt.

According to Anderson, M.K., Halls, S., & Martin, M. (2005), there are four classifications of sciatic pain including the following:

• Sciatic pain only: no sensory or muscle weakness

• Sciatic pain with soft signs: some sensory changes, mild or no reflex change, normal muscle strength, normal bowel and bladder function

• Sciatic pain with hard signs: sensory and reflex changes, and muscle weakness caused by repeated, chronic, or acute condition; normal bowel and bladder function

• Sciatic pain with severe signs: sensory and reflex changes, muscle weakness, and altered bladder function

Diagnosis of sciatic pain

Sciatic pain related to disc herniation can be diagnosed by a sports medicine professional with a thorough medical history and clinical evaluation. If the sports medicine professional notes sensory and motor deficits specific to the sciatic nerve, the goal for the professional is to determine the cause. This can be done using either a CT scan or an MRI to better differentiate the soft tissue structures and diagnose the exact cause of the pain.

Who gets sciatic pain?

Because a common mechanism for a disc injury is forward bending and twisting (because it places a large amount of strain on the disc), any sport that requires this type of movement may place athletes at risk for sciatic pain related to disc injury. Basketball is one sport that places athletes in positions that may cause a risk for herniated disc because of the demands of the sport.

For example, athletes in basketball may place themselves at risk for a disc injury because of their body position during rebounding. Athletes will jump, land and twist their trunk with elbows extended to keep defenders at bay. An intervertebral disc can be injured with this mechanism especially if the athlete has any forward flexion of the trunk at the time of trunk rotation. It is this combination of movements that can place the disc at risk for herniation.

According to Bahr, R. & Maehlum, S. (2004), sciatic pain associated with disc injury or degeneration is seen more in adults and elderly as compared to adolescent and youth athletes. One contributing factor to this is that degeneration of the disc over time can contribute to disc herniation in adults and older athletes.

Causes of sciatic pain

Sciatic pain may be caused by a number of structural problems and may be caused by either an acute (one time injury) or chronic (over time) mechanism of injury. A diagnosis of chronic sciatica may be indicated if there is no clinical improvement of symptoms after 2-4 weeks even with treatment (Bahr, R. & Maehlum, S., 2004).

Possible causes of sciatic pain may include the following:

• Herniated disc (protrusion of nucleus pulposus past annulus fibrosis impinging on sciatic nerve)

• Annular tear

• Spinal stenosis (narrowing of intervertebral foramen)

• Facet joint arthropathy

• Compression of sciatic nerve from piriformis muscle

Although there are a number of possible causes, the most common cause of sciatic inflammation is from herniation of lumbar discs at L4-L5 and L5-S1 (Anderson, M.K., Hall, S., & Martin, M., 2005).

Prevention for sciatic pain

Preventing sciatic pain associated with intervertebral disc injury should begin with focusing on the causes of disc injury and taking steps to prevent those types of injury. Because most disc injuries are caused by a combination of rotation of the spine while the spine is in flexion, prevention needs to focus on correct back mechanics and avoidance of motions that may place the spine at risk for injury.

As stated above, teaching an athlete how to find and maintain a neutral spine is one key to preventing disc injuries. If an athlete can maintain his/her spine in a neutral position during all activities, then the spine will be at a lower risk for injury.

Maintaining core strength is integral in maintaining a healthy back and preventing a number of sports injuries to the back. Core stabilization exercises can be performed by the athlete on their own.

Core stabilization exercises can also be performed with the assistance of a therapy ball.

A number of good core exercises can be performed with the aid of a therapy ball including:

• Supine leg lift: athlete balances with his/her upper back on the therapy ball and legs on the floor; athlete alternately lifts the legs off of the floor while keeping pelvis in neutral position.

• Bridging: athlete lies on floor with legs extended and feet on therapy ball; athlete then lifts hips off of floor as buttocks and abdominals are tightened. This exercise can be made more difficult by having athlete alternate leg lifts off of the ball.

• Ball lift: athlete lies on back and places therapy ball between feet; athlete lifts ball up off of floor while maintaining hips at 90 degrees of flexion while maintaining tight abdominals.

• Prone walk-out: athlete lies on top of ball with legs extended and ball placed at hips; athlete walks forward using arms until the ball is at the shins and then walks back. For an advanced version, the athlete can walk out and then perform a push-up before returning to starting position.

Treatment for sciatic pain

The treatments can range from altering body mechanics (to reduce pressure on the herniated disc) to immediate surgery depending on the presentation of symptoms. As with all acute injuries, the athlete should initially follow the sports injury treatment using the P.R.I.C.E. principle – Protection, Rest, Icing, Compression, Elevation.

Initial treatment for mild sciatic pain is to reduce the load on the spine by avoiding activities that cause pain including impact from compression (jumping/landing) forces, lifting, bending, twisting, prolonged sitting and standing (Anderson, M.K., Hall, S., & Martin, M., 2005).

Rest is essential initially in the acute stage of sciatic pain. The patient should be encouraged to eliminate activities that increase pain and adjust to activities that do not cause pain.

Ice packs can be applied to the injured area to reduce swelling and inflammation. Ice packs can be applied for twenty minutes every two hours for the first two to three days.

To assist in reducing any inflammation that may be present, a physician may recommend NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or oral corticosteroids (Bahr, R. & Maehlum, S., 2004). Stronger pain medication may be indicated if the athlete is having difficulty sleeping.

Educating the athlete as to correct posture and back mechanics is another important factor in treating sciatic pain associated with disc injury. Athletes need to be taught to protect their spine by lifting with their legs (using large muscle groups of the quadriceps, hamstring, and gluteals) rather than bending at the waist and relying on the much smaller muscles of the back to lift objects.

When lifting large objects, the object should be held close to the body at the midline. This position reduces the amount of torque placed on the low back and the small muscles of the back.

Last, rather than twisting the spine to turn, the athlete should keep the object at his/her midline and turn his/her feet to change directions. Following these simple rules can significantly reduce the risk of soft tissue injuries to the back.

As the symptoms resolve, the athlete can focus on spine and hamstring flexibility, and core strength and stabilization exercises of the spine during daily activities and sports. Athletes will need to focus on strengthening the muscles surrounding the core of the body including the abdominals, obliques, back extensors, and gluteal muscle groups. Below is a list of videos of hamstring stretches, core strength exercises, and stabilization exercises.

The athlete will need to correct any postural problems that may place the athlete at risk for injuries. Also important, the athlete should learn how to find and maintain neutral spine position (also known as pelvic neutral). The athlete may need the assistance of a sports medicine professional to learn how to find and maintain a neutral spine position.

Neutral spine position is a position maintained by the pelvis and lumbar spine in which the least amount of stress is placed on the lumbar spine. Once this position is found, the athlete should be able to find and hold it during all activities.

Progressive or persistent muscle weakness and radiating pain that does not diminish with time may be an indication for surgical intervention. Surgical intervention is also warranted if there is altered bladder or bowel function.

Recovery – Getting back to Sport

Depending on the severity of the initial injury, recovery from sciatic pain with associated disc injury may take anywhere from several weeks to six months (if neurological deficit is present).

Once the athlete is pain free in all movements of the spine with no neurological symptoms, the athlete can begin sport specific functional training. The purpose of this type of training is to gradually reintroduce the athlete to a program of increasing intensity to ensure that the injury has completed healed prior to releasing the athlete to return to play.

Along with ensuring that the injury has completely healed and that the body can withstand the demands of his/her sport, sport specific activity also allows the athlete an opportunity to regain the confidence that he/she once had in his/her body prior to being injured. Rebuilding confidence is as important to the athlete’s ability to return safely to sport as rehabilitating the actual injury.

Sport-specific functional exercises are the final phase of rehabilitation and should include every primary component of the sport that the athlete will need to accomplish. The only key is that the exercises be progressive and begin with low intensity effort and gradually progress to full-out contact over time.

The time that it takes for the athlete to progress to full intensity activities is dependent on the severity of the athlete’s initial injury and the confidence of the athlete to proceed. If the athlete is hesitant, then the sports medicine professional or coach should proceed at a slower pace and progress as the athlete is comfortable.

When Can I Return to Play?

The athlete can return to sports when he/she has been released by his/her sports medicine professional and when the athlete is pain-free and asymptomatic with all active movements.

Get a Virtual Sports Specialized appointment within 5 minutes for $29

When you have questions like: I have an injury and how should I manage it? How severe is it and should I get medical care from an urgent care center or hospital? Who can I talk to right now? SportsMD Virtual Urgent Care is available by phone or video anytime, anywhere 24/7/365, and appointments are within 5 minutes. Learn more via SportsMD’s Virtual Urgent Care Service.

When you have questions like: I have an injury and how should I manage it? How severe is it and should I get medical care from an urgent care center or hospital? Who can I talk to right now? SportsMD Virtual Urgent Care is available by phone or video anytime, anywhere 24/7/365, and appointments are within 5 minutes. Learn more via SportsMD’s Virtual Urgent Care Service.

References

Anderson, M.K., Hall, S.J., & Martin, M. (2005). Foundations of Athletic Training: Prevention, Assessment, and Management. (3rd Ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA.

Arnheim, D. &Prentice, W. (2000). Principles of Athletic Training. (10th Ed.). McGraw Hill: Boston, MA.

Bahr, R. & Maehlum, S. (2004). Clinical Guide to Sports Injuries. Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL.

Houglum, P. (2005). Therapeutic Exercise for Musculoskeletal Injuries. (2nd Ed). Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL.