Meniscus Tear in Knee

What is a meniscus tear?

A Meniscus tear in the knee is among the most common orthopaedic injury and has been colloquially referred to as “torn cartilage” in the knee. They have affected athletes of virtually every sport. While they are most commonly seen in the posterior horn, they can occur in any location and affect either the medial side, lateral side, or both.

In athletes, a meniscus tear usually is a traumatic origin. The result of abnormally high forces that fail the substance of the meniscus. While these are often the result of forceful twisting or pivoting movements, they can also occur with seemingly innocuous activities such as squatting or jogging. From baseball catchers to professional defensive lineman, virtually every sport and position player has been affected by this injury. Some names you will recognize include Osi Umeniyora, Johan Santana, Sedrick Ellis, and Shawne Merriman – all have battled meniscus tears in their athletic career.

In older patients, a meniscus tear may not be of traumatic origin but rather part of degenerative changes in the knee. These tears are often accompanied by some arthritic changes in the knee and are referred to as “degenerative” tears.

What are the menisci?

The menisci are pieces of cartilage in the knee that play a vital role in athletes. They are two C-shaped structures that lie between the femur and tibia on the inside (“medial”) and outside (“lateral”) aspects of the knee. They predominantly consist of water and collagen fibers. Historically, the function of the menisci was unclear, and some even considered them to be vestigial remnants of embryonic tissue like the appendix. For this reason, complete excision of the meniscus (“total meniscectomy”) was not infrequently performed in the setting of a symptomatic meniscus tear. Unfortunately, total meniscectomy in young patients has been shown to dramatically accelerate degenerative wear in the knee.

Critical functions of menisci

Various critical functions of the menisci to the maintenance of knee health have been well-established. These include:

• Load Transmission – the menisci are responsible for transmitting between 50% to 70% of the loads across the knee joint. In their absence, these loads are directly transmitted to the articular cartilage on the ends of the bones.

• Joint Stability – the menisci are secondary stabilizers of the knee in many planes, and become the primary stabilizer for front-to-back (“anteroposterior”) motion of the knee when the athlete suffers an anterior cruciate ligament (torn ACL).

• Shock Absorption

• Joint Lubrication and Nutrition

Anatomy of the menisci

The menisci are “wedge-shaped” pieces of cartilage that rest between the thigh bone (“femur”) and lower leg bone (“tibia”) in the knee joint. There are two menisci, a medial one on the “inside” of the knee and a lateral one on the “outside” of the knee. The medial meniscus is C-shaped, while the lateral meniscus is more semicircular in shape. Both rest on the tibial surface and are anchored to the bone at the front and back of the plateau (“meniscus roots”).

Each meniscus can be divided into portions based on (i) location within the knee, or (ii) blood supply. By location, the meniscus can be divided into a (i) posterior horn, (ii) body, and (iii) anterior horn. These terms are helpful to describe the location of meniscus tears. Tears in the posterior horn are the most common.

The blood supply of the meniscus comes from the periphery where it attaches to the lining of the knee joint (“capsule”). For this reason, the peripheral one-third of the menisci are generally well-perfused, while the inner aspects have a more limited blood supply and correspondingly limited potential for healing. These different locations moving from peripheral-to-central have been termed the “red-red”, “red-white”, and “white-white” zones. This classification becomes important when evaluating meniscus tears and considering their capacity for healing after a meniscus surgery.

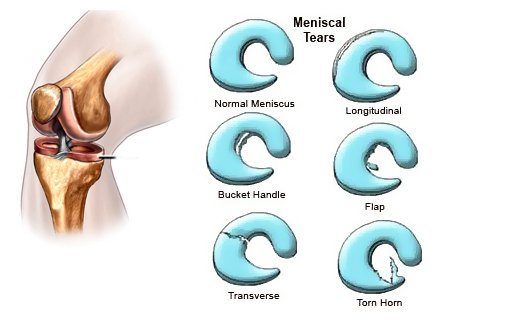

Meniscus tear types: Classifications

There are several types of meniscus tears and they can be classified in various ways – by anatomic location, by proximity to blood supply, etc. Various tear patterns and configurations have been described. These include:

• Radial tears

• Flap or Parrot-beak tears

• Peripheral, longitudinal tears

• Bucket-handle tears

• Horizontal cleavage tears

• Complex, degenerative tears

These tears can then further classified by their proximity to meniscus blood supply, namely whether they are located in the “red-red,” “red-white,” or “white-white” zones.

The functional importance of these classifications, however, is to ultimately determine whether a meniscus is REPAIRABLE. Given the critically important functions of the meniscus in athletes, it should be preserved and repaired whenever possible.

The repairability of a meniscus is dependent upon a number of factors. These include:

• Age

• Activity Level

• Tear Pattern

• Chronicity of the tear

• Associated Injuries (Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury)

• Healing Potential

Related injuries with meniscus tear

While a meniscus tear can certainly occur in isolation, they are often accompanied by other injuries in the knee as well. In the setting of high-energy trauma, associated fractures of the proximal tibia (“tibial plateau”) can occur. Meniscus tears have been reported to be as common as 50% with these fractures.

A meniscus tear often accompanies tears of the anterior cruciate and/or collateral ligaments as well. The posterior horn of the medial meniscus is the secondary stabilizer to anteroposterior translation of the joint, and therefore becomes particularly vulnerable to injury with deficiency of the anterior cruciate ligament (the primary anteroposterior stabilizer of the joint).

Symptoms – What does meniscus tear feel like?

A meniscus tear can present in various ways. Sometimes it feels like a “popping” sensation which is experienced by the athlete during a traumatic event.

Is meniscus tear painful?

There is usually significant pain along the joint line on the side of the meniscus tear (medial or lateral). Sometimes the athletes can continue to walk on the knee, while other large tears may cause too much pain to allow for weightbearing. Sometimes the tear pattern can cause a portion of the meniscus to become entrapped between the joint surfaces or within the notch of the knee. In these cases, the knee is often locked and the athlete cannot flex or extend the knee.

Meniscus tear signs include:

• Pain, often along the joint line of the knee

• Swelling (“effusion” in the joint) often develops due to inflammation and/or bleeding from the injury

• Inability to fully extend or flex the knee without discomfort

• Locking or catching of the knee

• Weakness of the leg, particularly the quadriceps muscle. This may be evident when trying to perform a straight leg raise or walk up and down stairs.

In addition to examining for the above signs and symptoms, a physician may check the athlete’s ability to squat on the knee without discomfort. The doctor may also perform a McMurray’ Test in which the knee is bent, straightened, and rotated in an attempt to entrap the meniscus tear within the joint. If you have a meniscus tear, this movement may reproduce clicking and pain.

Imaging studies

Plain x-rays (radiographs) of the knee can be useful to evaluate for the presence of associated injuries such as tibial plateau fractures or ligament avulsions. They will not, however, confirm or rule out the presence of a meniscus tear.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee has become the gold standard of imaging studies for a meniscus tear. These high-resolution pictures from multiple perspectives allow for a greater than 95% sensitivity in detecting a meniscus tear. Furthermore, they provide valuable information regarding the tear pattern and configuration to help preoperative planning and assessment of the repairability of the tear.

MRI of the knee not only helps to define the tear, but allows for evaluation of the other important anatomical structures of the knee. The status of the collateral and cruciate ligaments, as well as the cartilage surfaces of the joint can be carefully evaluated to help design the best treatment plan.

Treatment for Meniscus tear

With this increased appreciation of meniscus function, surgical techniques have focused on preservation and repair whenever possible in athletes. Arthroscopy has allowed for various repair strategies with minimal invasion and excellent visualization. However, the tear pattern must be repairable and the tissue have the ability to heal for a repair to be successful. In addition, the age of the athlete, expectations, and associated injuries must be considered as well. For this reason, no definitive set of guidelines can be provided for determining which tears should not be treated, which should be repaired, or which should be partially excised (“partial meniscectomy”). However, some good general principles include:

• Rim width is the most important prognostic criteria for healing after meniscus repair. Therefore, peripheral, longitudinal tears within 3-mm (“red-red” vascular zone) of the meniscocapsular junction should be repaired. Longitudinal tears within 3 to 6-mm width (red-white zone) have less predictable success, but should still be considered for repair in younger patients.

• Tears more than 6-mm from the peripheral blood supply are generally avascular and are not suitable for repair.

• Acute, traumatic tears have an improved prognosis for healing compared to chronic, degenerative lesions.

• Longitudinal tears are more amenable to repair than the flap, horizontal cleavage, or complex degenerative patterns.

• The management of the radial tear is controversial. Large radial tears extending to the periphery are technically easy to repair and should be considered for repair in young patients to restore hoop stresses and load transmission function of the meniscus.

• Age should not be used as an absolute criterion for determining the feasibility of repair. While younger patients have a more favorable prognosis, successful healing has been reported in older patients.

• Higher rates of failure have been noted in the setting of unstable knees secondary to excessive shear forces that prevent healing. Therefore, an insufficient anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) should be reconstructed at the time of meniscus repair. Reconstruction of the ACL at the time of meniscus repair has been associated with a more favorable rate of meniscus healing.

• Partial thickness tears that are shallow and stable (<3mm depth and <1cm length) generally heal spontaneously. Unstable partial thickness tears, however, should be repaired.

Get a Virtual Sports Specialized appointment within 5 minutes for $29

When you have questions like: I have an injury and how should I manage it? How severe is it and should I get medical care from an urgent care center or hospital? Who can I talk to right now? SportsMD Virtual Urgent Care is available by phone or video anytime, anywhere 24/7/365, and appointments are within 5 minutes. Learn more via SportsMD’s Virtual Urgent Care Service.

When you have questions like: I have an injury and how should I manage it? How severe is it and should I get medical care from an urgent care center or hospital? Who can I talk to right now? SportsMD Virtual Urgent Care is available by phone or video anytime, anywhere 24/7/365, and appointments are within 5 minutes. Learn more via SportsMD’s Virtual Urgent Care Service.

Meniscus Tear Surgery

If a meniscus tear is symptomatic and limiting the ability of an athlete to return to play, it is typically addressed with surgery. The vast majority of meniscus tear surgeries can be performed arthroscopically through small incisions in the skin. The camera is used to carefully visualize and define the tear pattern.

For irreparable tears, the torn fragments are typically excised and the residual meniscus smoothly contoured. Care is taken to preserve as much stable tissue as possible to retain the important load transmitting functions of the meniscus. For repairable tears, instruments are introduced to freshen the torn edges, line them up (“reduce” the tear), and suture the tear. Various techniques to suture the meniscus tear edges have been described. These fall into the general categories of repairing the tear from entirely within the joint (“all-inside”), from inside to out of the joint (“inside-out” repair), or from outside to in the joint (“outside-in”). Each technique has its associated strengths and limitations. Regardless of which is utilized, however, the ultimate goal is a well-reduced meniscus and secure repair across the torn edges.

If the blood supply to the location of the tear is tenuous, augmentation with substances to promote healing may be considered. Fibrin clot has been used with some efficacy in this regard. Platelet rich plasma augmentation at the site of the tear may be beneficial, and studies are currently in progress to evaluate its effects on meniscus healing.

Meniscus Tear Surgery recovery

Meniscus tear surgery recovery program is highly dependent upon the specific procedure performed as well as the specific nature of your tear. Your expectations and sport must be considered as well.

In general, partial meniscectomy for irreparable tears will allow for a more rapid recovery than meniscus repair surgery. This is because the interval time to allow for tissue healing is not required. After partial meniscectomy, weightbearing is gradually allowed as tolerated and exercises are initiated promptly to achieve full range-of-motion of the knee. Strengthening exercises are subsequently initiated. While time to return to sports is variable, a goal of 3 to 4 months is generally feasible.

For meniscus surgery, a period of non-weight-bearing and restricted range-of-motion is usually implemented postoperatively to optimize the environment for healing of the tissues. A range-of-motion and strengthening program is subsequently implemented. In general, a goal of 6 months to return to play is typical, but can be much longer depending upon tear severity and functional goals. More information on what is the reovery time for meniscus tear surgery.

Having a Torn Meniscus

Some helpful principles of meniscus repair rehabilitation include:

• The effect of tear configuration and knee range-of-motion on meniscus healing guide rehabilitation.

• Compressive loads on peripheral longitudinal tears with knee in extension typically reduce the tear edges.

• Compressive loads on peripheral longitudinal tears in flexion displace the posterior horn and tear edges.

• The menisci translates posteriorly with knee flexion, but minimally from 0 to 60 degrees. The lateral demonstrates more translation than the medial meniscus.

Some typical protocols for meniscus surgery repair are:

Peripheral, longitudinal tears: Hinged knee brace postoperatively locked in extension for 3-4 weeks. Partial weightbearing for 4 weeks with the brace locked in extension. Advance range-of-motion and weightbearing over 3-6 weeks. Sport-specific training and strengthening at 6-8 weeks. No running for 4 months.

Radial tears/Complex tears: Hinged knee brace postoperatively is locked in extension for 3-4 weeks. Toe-touch weightbearing for 4 weeks with the brace locked in extension. Range-of-motion and weightbearing are gradually advanced in the brace at 4-6 weeks.

I previously discussed playing through a meniscus tear when Pat Beverley injured his knee in 2014. Beverley ultimately underwent surgery. https://t.co/DOS71DEt7Y

— Jeff Stotts (@InStreetClothes) June 2, 2021

References:

1. Rangger C, Klestil T, Gloetzer W, Kemmler G, Benedetto KP. Osteoarthritis after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Am J Sports Med 1995;23:240-244.

2. Hede A, Larsen E, Sandberg H. The long-term outcome of open total and partial meniscectomy-related to the quantity and site of the meniscus removed. Int Orthop 1992;16:122-125.

3. Diduch DR, Poelstra KA. The evolution of all-inside meniscus repair. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine 2003;11:83-90.

4. King DJ, and Matava MJ. All-Inside Meniscus Repair Devices. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine 2004;12:161-169.

5. Medvecky MJ, and Noyes FR. Surgical Approaches to the Posteromedial and Posterolateral Aspects of the Knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2005;13:121-128.

6. Cohen DB, and Wickiewicz TL. The Outside-In Technique For Arthroscopic Meniscus Repair. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine 2003;11:91-103.