PCL Tear

Last Updated on October 22, 2023 by The SportsMD Editors

The PCL (posterior cruciate ligament) although not as well known as it’s close neighbor the ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) is a surprisingly commonly injured structure including PCL tear. PCL surgery success rate and other options are presented below.

Anatomy and function of the PCL

The PCL is one of the two major ligaments crossing (hence the term cruciate) in the center of the knee. It connects on the thigh bone (femur) at the front of the knee and attaches to the lower leg bone (tibia) at the back of the knee.

The “posterior” in PCL refers to it’s insertion on the back of the tibia. Although it appears as a single large ligament, on close inspection, there are normally 2 described bundles that the ligament is comprised of. These 2 bundles seem to have differing points of maximum tension during knee range of motion. This has implications on the technique of reconstructing the PCL. There are also 2 smaller ligaments associated with the PCL known as the meniscofemoral ligaments because they attach between the thigh bone (femur) where the PCL does and the menisci (shock absorbing tough cartilage located within the knee joint). These somewhat variable structures provide significant additional strength to the function of the PCL.

The PCL is an extremely strong ligament and is in fact 1.5 times the size of the more commonly discussed ACL. The main role of the PCL is to keep the ends of the 2 bones of the knee (tibia and femur) centered on each other during normal knee activities. Specifically, the PCL resists backwards motion of the lower leg. Unlike the ACL, which is mainly functional during certain high-risk athletic activities, the PCL is important and is functioning almost all the time even during simple walking.

What else may be injured along with a PCL tear?

A PCL tear may occur in isolation, however worse injuries and those that often involve a twisting motion during the injury can damage other structures within the knee. The most important of this involves tearing other ligaments in the knee, such as a torn ACL or the outside (lateral) ligaments of the knee. When this occurs, the injury is no longer considered an isolated PCL tear and has a much higher chance of requiring advanced surgical treatment.

Who most commonly suffers a PCL tear?

An athlete in almost any sports is susceptible to a PCL tear especially if it’s one where there is a risk of contact to their lower leg. Common examples would include soccer, rugby and most frequently football. In fact 2% of all NFL combine attendees have evidence of a PCL tear at some point in the past. There are an estimated 20 PCL injuries each season in the NFL. They more commonly occur during game competitions. The great majority of these injuries do not require surgery to reconstruct the knee. Similarly, PCL tears make up about 5% of all knee injuries in rugby.

Just in the past year many notable NFL athletes have had a PCL tear such as Reggie Bush of the New Orlean’s Saints and Felix Jones of the Dallas Cowboys neither of whom required surgery. On the other hand, San Diego Chargers outside linebacker Shawne Merriman sustained a PCL injury complicated by an associated lateral (outside of the knee) ligament injury that he was unable to play with and had to undergo extensive surgical treatment on.

PCL Tear Symptoms

An athlete will describe a history of being struck on the front of the lower leg, falling directly onto the knee with the knee bent or a hyperextension injury as described previously. Often an experienced athletic trainer who is present at the injured athlete’s practice or competition will recognize the mechanism of injury as it occurs. Unlike with an ACL injury, during a PCL tear there is usually no audible “pop” heard.

Immediately following the injury, PCL Tear Symptoms will present swelling in the knee (effusion) from bleeding into the knee from torn blood vessels in the injured ligament. The acute injury will be painful and the patient may hold their knee slightly bent for comfort. The pain experienced may also be in the back of the knee depending on the location of the tear. In the case of an older tear that occurred long prior to evaluation, the patient may complain of instability, or a sensation of the knee giving away. They may also complain of pain which can be in the front of the knee as well.

When examined, the hallmark of a PCL tear is that the lower leg (tibia) sags backwards with respect to the end of the thigh bone (femur). How much the tibia sags depends on the severity of the injury and has major implications in treatment as will be discussed below. There may also be evidence of further instability if other ligaments are injured as seen in more severe injuries. This may cause abnormal rotation of the knee on exam in a plane corresponding to the additionally injured structures. If an ACL injury is present as well, then the tibia will be loose when pulled forward (Lachman test).

Classifications of PCL tear

A PCL tear is classified in a couple of different ways. One simple way is to describe them as either an isolated PCL tear, where only the PCL is injured, or as a combined ligament injury. A combined ligament injury would involve a tear of the PCL and at least one other injured ligament. A common example would be a PCL and lateral-sided ligament injury as occurred with Shawne Merriman.

Injuries to the PCL can also be graded as I, II or III. Grade I and II injuries are partial PCL tears.

- Grade I refers to only a few mm of sag of the tibia backwards

- Grade II injuries refer to sagging of the tibia to the level flush with the end of the thigh bone (femur). This roughly corresponds to 1 cm of backwards sag.

- A grade III injury signifies a complete rupture and the tibia sags backwards even further. It is likely that when a grade III injury occurs, there are other ligaments torn along with the PCL. It is important to scrutinize the type of PCL injury an athlete sustains because there are significant treatment implications, especially for a Grade III or combined ligament injury.

Causes

A PCL tear occurs when a direct blow to the front of the knee or leg just below the knee (tibia) creates a large sudden force directed backward. This puts a significant amount of stress on the PCL. The stress in the ligament is even higher when the knee is flexed (bent) closed to 90°. The posterior cruciate ligament then stretches to the point of mechanical failure which is considered a tear. This can happen when someone is tackled in football below the knee from the front or when someone in any sport lands forcefully directly onto their knee with their knee simultaneously bent. The PCL can also tear in this manner when in a head-on motor vehicle collision the vehicle’s dashboard strikes directly against the knee.

Sometimes the PCL can be stretched and subsequently torn by forceful hyperextension (bending backward beyond straight) occurring to the athlete’s knee. This may occur when, in football, a player is hit on the legs just below the knee from the front and their knee hyperextends because their foot is firmly planted in the playing surface. This mechanism, especially when the knee twists during the injury, can lead to tearing of other important knee structures beyond simply the PCL.

Treatment for PCL Tear

Initially, sports injury treatment using the P.R.I.C.E. principle – Protection, Rest, Icing, Compression, Elevation can be applied to a PCL tear.

A partial PCL tear, grade I and II, are typically treated non-operatively with a long course of intensive physical therapy to strengthen the surrounding muscles controlling the knee.

Complete PCL tears often require surgical treatment to regain knee stability. When the PCL pulls off a small piece of bone from the back of the lower leg (tibial avulsion), the PCL may be surgically repaired. If the bone fragment is large enough a screw can be placed to secure the piece of avulsed bone back to where it was originally. However in the majority of PCL injuries, the ligament tears in the middle of the structure. In this case, the PCL must be reconstructed which refers to replacing the entire ligament with what is known as a graft.

Treatment when other injuries present

When a combined ligament injury is present, the treatment is almost always surgical. All injured structures that do not heal must be addressed at surgery, otherwise the PCL reconstruction will be at a high risk of failing once the athlete returns to sports participation. In this circumstance it is important that the injured athlete be evaluated by a sports medicine trained orthopaedic specialist as surgical treatment of these injuries can be highly complex and pose significant risk to major nerves and arteries around the knee.

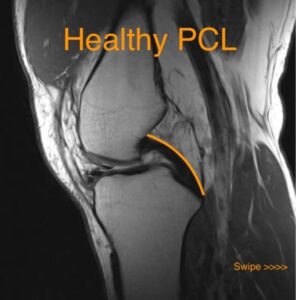

PCL Tear MRI and X-Ray

Standard knee Xrays and MRI’s are always important to obtain. These are needed to rule out fractures and look for evidence of other injuries that may be present. When a PCL injury is longstanding, present for years, there is a propensity for the knee to develop arthritis. This is especially the case beneath the knee cap (patellofemoral joint) and on the inside of the knee (medial side). Xrays can see narrowing of a joint and bone spurs that are indicative of arthritis associated with an old PCL injury. Sometimes obtaining a side xray (lateral view) with a backward force on the lower leg, known as posterior stress views, is useful to quantify the amount of backward sag. This can sometimes help grade the injury more accurately.

out fractures and look for evidence of other injuries that may be present. When a PCL injury is longstanding, present for years, there is a propensity for the knee to develop arthritis. This is especially the case beneath the knee cap (patellofemoral joint) and on the inside of the knee (medial side). Xrays can see narrowing of a joint and bone spurs that are indicative of arthritis associated with an old PCL injury. Sometimes obtaining a side xray (lateral view) with a backward force on the lower leg, known as posterior stress views, is useful to quantify the amount of backward sag. This can sometimes help grade the injury more accurately.

An MRI is useful to evaluate the ligamentous structures of the knee, not just the PCL. It can also evaluate the menisci and the cartilage surfaces of the knee for arthritis. When a PCL injury has just occurred, the PCL will look torn on the MRI. However the PCL has a remarkable ability to heal itself and the farther out from the injury an MRI is performed, the less remarkable the PCL will appear on the MRI. In fact an old PCL injury that occurred months or years ago may show up as normal on an MRI despite clear evidence of a PCL injury on clinical exam.

Non-operative treatment

Non-operative treatment of a partial PCL tear involves a period of immobilization of the knee followed by intensive treatment by a skilled physical therapist. A short period of immobilization of the knee in a brace or even sometimes a cast may be necessary to allow the PCL to heal first. Early emphasis in physical therapy is on reducing knee swelling and obtaining full knee range of motion. Following this, the focus of physical therapy becomes strengthening the surrounding musculature of the knee which provides dynamic stabilization. Most importantly is quadriceps strengthening because they pull the tibia in a forward (anterior) direction and therefore counteract the backward sag of the tibia seen when a PCL is torn. Also, core and hip stabilization are important to regain maximum control over the entire lower extremity. This also helps develops this muscular control for their sport and maximize athletic performance.

PCL Tear recovery time without surgery

In many cases, an injured athlete with a PCL sprain and low-level tears such as grade 1 and grade 2 tears, have minimal damage to the ligament and can recover within 2-6 weeks, with no need for surgery. This may be shorter or longer depending on how severe the injury is and how well the athlete responds to therapy. More severe injuries such as grade 2 and grade 3 PCL tears will take 3-4 months. If surgery is needed the recovery may be 6 to 12 months of rehabilitation. Most PCL injuries can be managed without surgery, but with high-grade injuries, with instability, you may be advised to use a brace for the first 6 weeks of healing. A PCL brace will hold the tibia forwards, keeping the ligament out of a stretched position to encourage it to heal well in a short and tight position.

PCL Tear Surgery

In most cases of a complete PCL injury, surgical treatment is performed. Most commonly this requires removal of the torn ligament and a new ligament to be reconstructed in the old ligament’s place. The new ligament graft can be from many sources, however most commonly it is an allograft (tissue graft from a cadaveric donor). Which specific allograft tissue is up to the discretion of the operating surgeon and may be taken from one of various tendons of the ankle or from the quadriceps tendon at the knee. Then the injured PCL is removed with the help of the arthroscope (small camera) using a few very small incisions. Any other associated cartilage and meniscus injury can be treated at the same time. Then a tunnel is created in the end of the thigh bone (femur) where the PCL attaches. The bone where the PCL attaches to the back of the lower leg (tibia) is also prepared to receive the graft. The new PCL graft is then connected to the bone at each end with one of various fixation devices (screws or staples) and therefore recreates the PCL. Because much of the surgery for a PCL reconstruction is performed in the back of the knee, there is a greater risk of a nerve or blood vessel injury than in most knee surgeries. It is important that an athlete is checked both during and after surgery that damage to one of these important structures did not occur.

There are some hotly debated controversies in PCL reconstruction. These involve whether a single large graft or a double-bundle graft with 2 smaller limbs should be used. There is some evidence the double-bundle graft may be mechanically stronger. However, there has been no clinical evidence that patients do better with one versus the other.

Another controversy involves how the graft is attached to the back of the tibia. One technique involves performing the surgery almost entirely through the small incisions with the help of the arthroscope. The other technique (tibial inlay) involves making a larger incision at the back of the knee and directly attaching the new PCL graft at that point. There is some evidence that performing the surgery in this manner is more mechanically advantageous to the graft. The graft might not be stretched as much and may have a lower rate of failure. The ideal technique of PCL reconstruction may vary somewhat on a case by case basis and therefore would normally be discussed with the treating sports medicine surgeon.

PCL Surgery success rate

The success rate of PCL grafts is reported in the literature from 75-100% (the average being about 85%).

The graft can fail for any number of reasons:

- Return to sports activity or work to quickly

- Re-injury or trauma to the knee

- Surgeon error

- Failure of fixation (the button and screw keeping the graft in place)

- Failure of the graft to heal

PCL Tear recovery time after surgery

Recovery following surgical treatment of a PCL tear requires a long course of physical therapy and can take up to 6 months to a year of rehab to fully recover. Initial treatment focuses on regaining range of motion and decreasing the swelling in and around the knee. Early quadriceps retraining is very important to regain control of the knee. Then over the course of months the rehab is progressed to a functional program with a goal of returning an athlete to their sport. Early on in returning to sports participation, an athlete may wear a protective brace although for how long is determined by the surgeon who performs the surgical reconstruction.

Professional athletes with PCL Tears

Just a reminder that a Grade 2 PCL sprain is at least a partial tear of the ligament in the back of your knee that connects your thigh bone to the lower leg bones. A Grade 3 is a complete tear. I think people hear the word “sprain” and might not realize how severe the injury is. https://t.co/oJG1dyKfV4

— Luke Easterling (@LukeEasterling) January 12, 2023

Get a Telehealth Appointment or Second Opinion With a World-Renowned Orthopedic Doctor

Telehealth appointments or Second Opinions with a top orthopedic doctor is a way to learn about what’s causing your pain and getting a treatment plan. SportsMD’s Telehealth and Second Opinion Service gives you the same level of orthopedic care provided to top professional athletes! All from the comfort of your home.. Learn more via SportsMD’s Telemedicine and Second Opinion Service.

Telehealth appointments or Second Opinions with a top orthopedic doctor is a way to learn about what’s causing your pain and getting a treatment plan. SportsMD’s Telehealth and Second Opinion Service gives you the same level of orthopedic care provided to top professional athletes! All from the comfort of your home.. Learn more via SportsMD’s Telemedicine and Second Opinion Service.

References

Wind WM Jr, Bergfeld JA, Parker RD. Evaluation and treatment of posterior cruciate ligament injuries: revisited. Am J Sports Med. 2004 Oct-Nov;32(7):1765-75.

Parolie JM, Bergfeld JA. Long-term results of nonoperative treatment of isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries in the athlete. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14:35-38.

Matthew J. Matava, Evan Ellis, and Brian Gruber. Surgical Treatment of Posterior Cruciate Ligament Tears: An Evolving Technique J. Am. Acad. Ortho. Surg., July 2009; 17: 435 – 446.

Shelbourne KD, Davis TJ, Patel DV. The natural history of acute, isolated, nonoperatively treated posterior cruciate ligament injuries: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:276-283.