Stingers and Burners | Brachial Plexus

Last Updated on October 20, 2023 by The SportsMD Editors

A stinger or burner is actually an injury to a group of nerves known as the brachial plexus that include the nerve roots extending from spinal vertebrae C5 and continuing through T1. These nerve roots originate from the spinal cord and branch out from the spinal cord at the levels of the various vertebrae (i.e., C5 is at the level of the 5th cervical vertebrae).

The individual nerve roots from C5 through T1 converge to form the brachial plexus as they move from the neck into the shoulder. Although they converge into a tight bundle above the shoulder, they diverge into separate nerve branches as they travel down the arm.

Each individual nerve root is responsible to innervate different muscles of the shoulder, arm, forearm, and hand and innervate different dermatome (skin surface areas) patterns. Injuries to individual nerve roots will result in associated deficits to the muscles and/or dermatome patterns that they innervate. However, injury to the brachial plexus may result in symptoms that affect the entire arm rather than just one portion.

The goal during the immediate assessment of the athlete with a suspected brachial plexus injury is to determine if the athlete has a spinal cord injury or a brachial plexus stinger. The primary difference is that a spinal cord injury will affect both the right and left side of the athlete equally whereas a brachial plexus stinger affects only one side of the body. If there is any doubt about the specific injury, the athlete should be immediately stabilized on the field and emergency medical services called.

What are stingers and burners?

A brachial plexus stinger is an injury to the nerve bundle that results in transient paralysis and paresthesia (loss of sensation) of the entire arm. Although frightening for the athlete, the transient paralysis and paresthesia usually resolves quickly within minutes. However, more serious brachial plexus stingers can result in damage to the nerve itself with neurological deficits lasting up to one year.

Classifications of stingers and burners

Regardless of the classification of the injury, the athlete will experience similar type of symptoms including “sudden, severe burning pain that radiates” down the arm and may have associated “degrees of numbness, weakness, and neck pain” (Irvin, R., Iversen, D., & Roy, S., 1998).

There are three classifications of brachial plexus stingers beginning with the mildest classification as a Grade I injury and progressing in severity through to a Grade III injury.

Grade one stinger or burner:

Grade one injury is called a neuropraxia injury and results in a temporary loss of sensation and/or loss of motor function (ability to use muscles). This is thought to occur due to a localized conduction block in the nerve bundle that prevents the flow of information from the spinal cord to the innervated areas. Because this is only a “block”, the symptoms are transient and may only last from several minutes to several days.

Grade two stinger or burner:

Grade two injuries are more significant injuries because there may be actual damage to the nerves known as axonotmesis. Axonotmesis is defined as damage to the axon of the nerve without severing the nerve (Anderson, M.K., Hall, S.J., & Martin, M., 2005).

These types of injuries may produce significant motor and/or sensory deficits that last at least two weeks. Because growth of an injured axon is a very slow process (a rate of 1 to 2 mm per day), it takes several weeks for the regrowth to occur. However, once the regrowth has occurred, full function of the athlete’s motor and sensory functions are restored (Anderson, M.K., Hall, S.J., & Martin, M., 2005).

Grade three stinger or burner:

The most severe plexus injury is a grade three injury. Athletes with these types of injuries may not have a full recovery and may be considered to have sustained a catastrophic injury because the neurological symptoms may last up to one year.

A Grade III is known as a neurotmesis injury and is defined as a complete severance of the nerve. Athletes who have sustained this type of injury have a poor prognosis and may need surgical intervention.

Diagnosis for stingers and burners

Any athlete sustaining an injury with neurological symptoms needs to be referred to a sports medicine professional for a complete medical evaluation. The athlete will undergo a complete medical history evaluation along with clinical and neurological tests including both motor and sensory tests. The physician may also order an x-ray to rule out any bone injury of the cervical spine.

Who gets stingers and burners?

Brachial plexus stingers are well known and common in the sport of football but are rarely seen in any other sport (Brukner, P. & Khan, K., 2002). It is not uncommon to have a football player run off the field with his/her arm hanging limply to the side during a practice and/or game. They are common in the sport of football because of the frequency that the athletes lead with their heads and shoulders.

Causes of stingers and burners

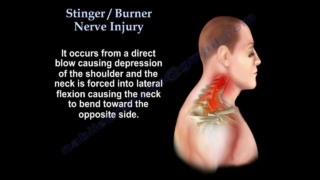

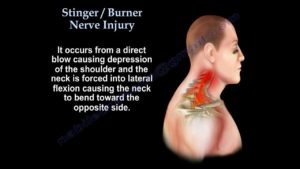

Although brachial plexus stingers have several mechanisms of injury, the most common is when the brachial plexus is stretched when the head is forced to one side while the opposite shoulder is depressed. This “stretch” is enough to cause a temporary injury to the plexus resulting in transient symptoms of the shoulder, arm, and hand.

This nerve bundle can also be injured through a direct blow to the side of the neck/shoulder or injured when the neck is extended (face to the sky) while the shoulder is abducted (arm is moved up and to the side of the body). During this type of positioning of the head and shoulder, the brachial plexus can be compressed between the clavicle and first rib.

Preventing stingers and burners

Maintaining and improving neck musculature year round is one way to reduce neck injuries in athletes competing in contact sports. Regardless of the position that the athlete plays on the field, all players competing in contact sports should work on improving strength, power, and endurance in the muscles surrounding the neck.

Proper technique is another area coaches can focus on to reduce the incidence of neck injuries. Specifically, football players need to be taught the correct techniques of blocking and tackling without leading with their heads.

Treatment for stingers and burners

Management of a brachial plexus stinger is dependent on the length of time that the athlete experiences his/her symptoms. Initially, the athlete should be removed from competition.

A certified athletic trainer is trained in the administration of neurological tests that isolate motor and sensory nerves to determine if there is a deficit in one or more nerves. These professionals would be able to determine if there is a brachial plexus injury or a nerve root injury on the sideline.

If a brachial plexus stinger is suspected, the athlete should be retested periodically on the sideline to determine if the symptoms have resolved. According to Anderson, M.K., Hall, S.J., & Martin, M. (2005), athletes whose symptoms have completely resolved within five minutes may be returned to play.

This means that the athlete would need to have full strength in all affected arm muscles equal to the uninjured side with no associated neurological (burning, numbness, or tingling) symptoms. Even if the athlete is able to return to play on the same day, the athlete should be followed carefully throughout the remainder of the game and retested post game.

If symptoms do not resolve, the athlete needs to proceed with following sports injury treatment using the P.R.I.C.E. principles Protection, Rest, Icing, Compression, Elevation- to help reduce inflammation and pain around the injured nerves. Ice packs can be applied to the neck/shoulder area for twenty minutes every two hours for the first two to three days. The athlete should eliminate any activities that may aggravate the condition (excessive head/neck motions with associated arm motions) and rest if possible.

Because of possible damage to the nerves, strength training is contraindicated early during rehabilitation. The initial phase of rehabilitation should begin with range-of-motion exercises for the neck while the athlete is in a supine position (lying down face up). Range-of-motion exercises are easier to perform in this position because the neck muscles are not engaged in maintaining the position of the head.

The athlete should work on flexion (chin to chest), rotation (chin to shoulder), and lateral flexion (ear to shoulder). All range-of-motion exercises should be performed slowly and through pain-free ranges.

Along with range-of-motion exercises for the neck, range-of motion exercises for the shoulder also need to be performed. These exercises should also be performed slowly and only through pain-free ranges. All movements of the shoulder need to be included over time including:

• Flexion (raising arm in front of the body)

• Extension (returning arm from flexion position)

• Abduction (raising arm out to the side)

• Adduction (returning arm from abduction

• Internal rotation (rotation inward)

• External rotation (rotation outward)

• Horizontal abduction (bringing arm across the chest at shoulder level)

• Horizontal adduction (returning arm from horizontal adduction position)

• Diagonal adduction (throwing motion beginning with arm abducted, extended, and externally rotated)

As the range-of-motion of both the neck and shoulder improve, isometric muscle exercises for the neck can be started. Isometric exercises are unique in that the muscles contract but with no associated movements. For example, the athlete can lay on his/her back and push his/her head back against the surface object. This engages the muscles of the neck, but with no movement of the head.

Isometric muscle exercises are the first level of strengthening exercises. As the athlete improves in strength, the athlete can move to concentric muscle exercises. These are exercises that apply resistance through a specific range-of-motion. For the head/neck, the athlete can apply their own resistance.

For example, to increase the strength of the muscles in the back of the neck, the athlete can begin in a position with his/her chin on his/her chest. The athlete then places his/her hands on the back of the head and applies a light resistance as the athlete moves his/her head through extension.

The benefit of this type of exercise is that the athlete can apply as little or as much resistance as is comfortable. The goal is to apply enough resistance to engage the muscles and allow the head to move through the full range of motion. As the athlete’s muscles get stronger, more resistance can be applied.

Because nerve injuries heal slowly, patience is a characteristic that needs to be encouraged for this type of injury. Nerve injuries do not heal with more rehabilitation exercises. They will heal at their own rate regardless of the exercises performed. In the case of a brachial plexus nerve injury, more exercises are not better.

Recovery – Getting back to Sport

Once the athlete has pain-free full range-of-motion of his/her neck and shoulder and has complete strength equal to the uninjured side with no associated neurological symptoms, the athlete can then begin sport specific functional training to prepare the athlete for re-entry into sports.

The purpose of sport specific functional exercises is to gradually expose the athlete to the demands of his/her sport to ensure that the athlete’s body has fully recovered and to build confidence in the athlete to perform those skills.

First, the sport should be analyzed to make a list of the fundamental skills. Once the skills have been determined, the athlete should be asked to perform a series of them beginning at a low intensity and then gradually increasing the intensity over time.

Initial skills should be performed as non-contact drills progressing to contact drills once the athlete is confident and comfortable performing the skills at full speed. Once the athlete can perform the skills at full intensity, the athlete can then proceed to scrimmage situations.

Athletes returning to football with a history of brachial plexus stingers should be fitted with a neck collar to prevent lateral flexion and hyperextension injuries. All protective equipment should be carefully measured and custom-fitted to ensure that the athlete gets the most protection from the equipment.

When Can I Return to Play?

The athlete can return to play when he/she has been released by his/her physician and has met the following criteria:

• No neck pain, arm pain, or impairment of sensation

• Full pain-free range-of-motion of the neck and shoulder

• Normal strength on manual muscle testing as compared to the uninjured side

• Normal deep tendon reflexes

• Negative brachial plexus traction test

Get a Telehealth Appointment or Second Opinion With a World-Renowned Orthopedic Doctor

Telehealth appointments or Second Opinions with a top orthopedic doctor is a way to learn about what’s causing your pain and getting a treatment plan. SportsMD’s Telehealth and Second Opinion Service gives you the same level of orthopedic care provided to top professional athletes! All from the comfort of your home.. Learn more via SportsMD’s Telemedicine and Second Opinion Service.

Telehealth appointments or Second Opinions with a top orthopedic doctor is a way to learn about what’s causing your pain and getting a treatment plan. SportsMD’s Telehealth and Second Opinion Service gives you the same level of orthopedic care provided to top professional athletes! All from the comfort of your home.. Learn more via SportsMD’s Telemedicine and Second Opinion Service.

References

Anderson, M.K., Hall, S.J., & Martin, M. (2005). Foundations of Athletic Training; Prevention, Assessment, and Management. (3rd Ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA.References

- Brukner, P. & Khan, K. (2002). Clinical Sports Medicine. (2nd Ed.). McGraw Hill: Australia.

- Irvin, R., Iversen, D., & Roy, S. (1998). Sports Medicine: Prevention, Assessment, Management, and Rehabilitation of Athletic Injuries. Allyn and Bacon: Needham Heights, MA.